This book was a major disappointment and had major flaws in The Tudors section. First off, Henry VII was basically skipped over, no picture -- the Tudors section starts with the portrait of Elizabeth I. According to the author "Henry Tudor's blood was barely blue being five generations from Edward III" and "Henry was not born to the crown" -- the latter being true, but to skip such an important figure along with Elizabeth of York is unforgivable.

|

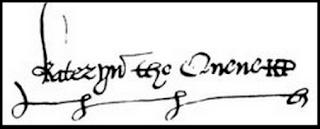

| Image thought by some, uh who, to be Anne Boleyn |

I also disliked how Catherine Parr's section was full of errors and made her look like a harlot after the death of Henry VIII.

First off, there is no proof that Catherine was romantically involved [meaning sleeping with] with Thomas Seymour before the death of Lord Latimer or before the marriage of Henry and Catherine. Also, Thomas was sent away on business for the king, he didn't make himself scarce.

The statement that four out of six wives were redheads is incorrect.

Historians are not 100% sure that Catherine was part of Lady Mary's household.

The discussion of theology became a problem when Catherine started preaching to the King -- after the whole scandal they continued talking about religion, but it was more toned down.

I'm not sure where the info is coming from that Henry told his physician that he wanted to "get rid of" Catherine Parr. There were rumors, set up most likely by the Catholics at court, which also included Henry wanting to marry the Dowager Duchess of Suffolk, Queen Catherine's friend, who was even more prone to speak her mind when it came to matters of religion. There was no doctor involved in telling Queen Catherine about Henry's intentions. A warrant was drawn up which was taken to Queen Catherine. She went to King Henry arguing that she was "but a woman" and that she was merely trying to distract the King from his infirmities.

Catherine pushed Henry's wheelchair in the gardens?? The correct info has the two sitting in the garden when they were approached by Henry's guards.

Catherine pushed Henry's wheelchair in the gardens?? The correct info has the two sitting in the garden when they were approached by Henry's guards.The Queen Dowager, Catherine, waited a few MONTHS, not weeks, before re-entering into her "relationship" with Seymour. I don't think Catherine would have been that disrespectful, but just to be clear -- the King gave her the go ahead to re-marry who she wanted. They were thought to be married in the spring months, possibly May of that year.

Where the statement that Catherine was acting like a "trollop" came from, I would love to know. Seymour asked the King for permission to marry the Dowager Queen. Yes, Lady Mary was upset and thought Catherine should have waited a tad longer but in the two biographies I've read on Mary (Anna Whitelock and Linda Porter) she never once called Catherine a trollop. In fact, Mary disliked Seymour more than anything as he pestered her about matters of state. Mary eventually came to forgive Catherine -- Catherine received a letter from Mary while she was pregnant and Catherine named the baby girl after her step-daughter.

The stories of Seymour and Elizabeth are quite interesting and many theories have been put out there, but what actually happened in that household is another story as Elizabeth's lady, Kat Ashley, was the main contributor to the testimony. Kat herself encouraged Elizabeth to flirt with Seymour and had a crush on him herself. "But the doctor's dirty hands caused an infection"... there are many contributing factors to the fever that caused Catherine to die, much like the death of Jane Seymour. And the last sentence of Lady Jane being raised as a surrogate daughter -- she was a ward. This book and this chapter reads more like a romance novel then an actual history book.

The author put an actual biography of Catherine Parr (Susan James) within her chapter full of sources that is actually well respected; perhaps the author should have actually read the book before "quoting" it.

The chapter on The Tudors reads more like a romance novel than a history book; that might explain why the author chose the "romanticized" portrait of Anne Boleyn. No citations are given as to where the info comes from and major mistakes were made. The only good thing about the book is the reproduction of one of Anne Boleyn's letters and the letter from Katherine Howard to Master Culpepper.

One positive note the author made about Catherine Parr:

"Perhaps the most mature and educated of Henry's wives."